Introduction

The common cold may seem trivial, but its impact on global productivity and individual well-being is far from minor. Characterized by symptoms like nasal congestion, sore throat, and coughing, the cold is a self-limiting upper respiratory illness caused by viral infections. Though mild in most cases, it can exacerbate existing chronic diseases and occasionally lead to complications like pneumonia. This guide outlines the definition, epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment strategies for the common cold using the latest clinical evidence.

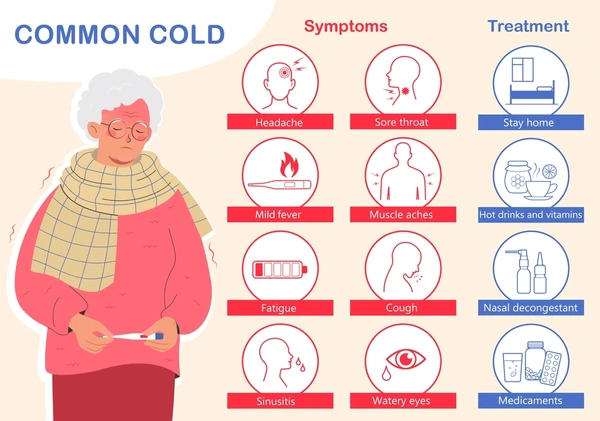

1. Definition, Symptoms, and Diagnosis of the Common Cold

Definition

The common cold is an acute viral infection localized to the upper respiratory tract. It is self-limiting and typically resolves within 10 days. Common symptoms include nasal congestion, runny nose, sore throat, sneezing, headache, cough, and general discomfort.

Causative Agents

- Rhinovirus (RV)

- Coronavirus

- Influenza and Parainfluenza viruses

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)

- Adenovirus, Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV)

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae

Diagnosis

In healthy individuals, diagnosis is clinical and based on symptom assessment. Imaging and lab tests are not routinely recommended unless:

- Fever exceeds 38°C

- Suspected pneumonia or heart failure

- Immunocompromised state

- Exposure to toxic substances

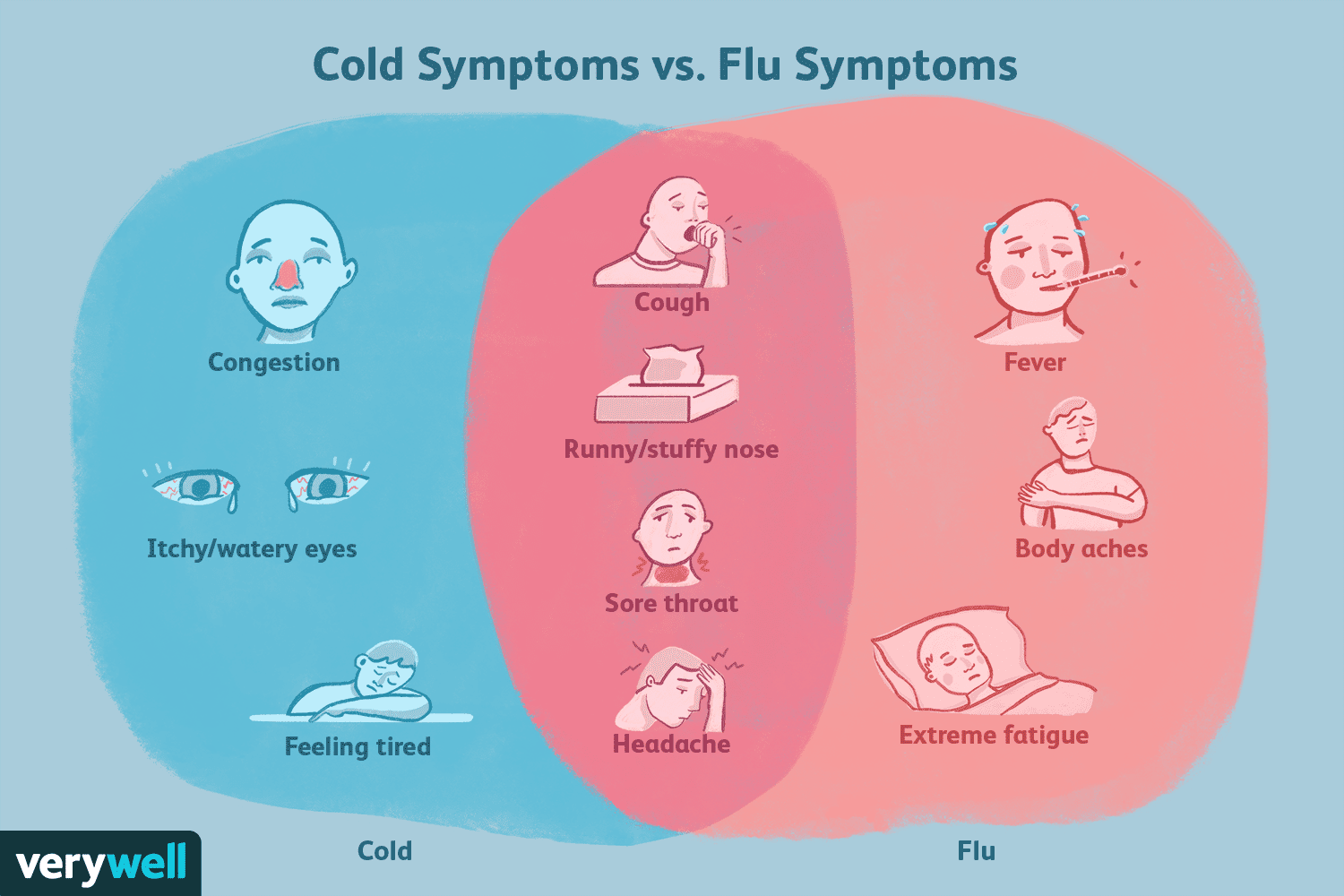

Differential Diagnosis

It is essential to differentiate the common cold from:

- Allergic rhinitis

- Acute bacterial sinusitis

- Influenza

- COVID-19 (especially Omicron and Delta variants)

2. Epidemiology of the Common Cold

Cold viruses affect all age groups but are more frequent in children and young adults. In the U.S., adults experience 2–3 colds per year on average. Economic burdens include:

- $6 billion in direct costs (USA)

- 27 billion Euros in lost productivity (Europe)

- Up to ¥300 in single prescription costs in major Chinese cities

3. Treatment of the Common Cold

A. Antiviral Therapy

Routine antiviral use is not recommended in healthy adults. However:

- Ribavirin is reserved for RSV in immunocompromised patients via nebulization.

- Neuraminidase inhibitors (e.g., oseltamivir) are effective during flu season for high-risk groups.

- Baloxavir and Arbidol (Umifenovir) may reduce symptom duration in confirmed flu or COVID-19 cases.

B. Micronutrient Therapy

- Zinc lozenges (≥75 mg/day) are effective if taken within 24 hours of symptom onset. Avoid nasal sprays due to risk of anosmia.

- Vitamin C may benefit physically stressed individuals in cold climates (e.g., athletes, soldiers).

- Vitamin D supplementation is recommended for those deficient to prevent viral infections.

- Vitamin E is not routinely recommended unless deficient.

C. Symptomatic Management

- NSAIDs (e.g., acetaminophen, ibuprofen) are effective for fever and aches.

- OTC cold medications may offer relief but carry risks; avoid those with phenylpropanolamine (PPA).

- Acute cough relief (CACC): Consider honey-based syrups or dextromethorphan. Refrain from using codeine derivatives like pholcodine in patients with neuromuscular exposure in the past 2 years.

D. Bacterial Coinfection

- Antibiotics are not recommended during the first 5 days unless: Symptoms worsen after initial improvement Unilateral facial pain or purulent discharge Elevated CRP or PCT levels

- If ABRS is suspected, use: Amoxicillin ± clavulanate Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime Levofloxacin (if resistant) MRSA-suspected: Vancomycin, linezolid

4. At-Risk Populations

Increased vigilance is needed for:

- Elderly (>65 years)

- Pregnant women

- Patients with chronic conditions: COPD, asthma, CHF, renal/liver impairment

- Immunocompromised individuals

5. Drug Development Landscape

As of June 2025, over 280 candidate drugs targeting the common cold are in various stages of clinical development. Leading candidates focus on broad-spectrum antivirals, novel capsid inhibitors, and symptom-specific therapies.

Conclusion

The common cold, while often benign, can trigger serious complications in vulnerable populations. Evidence-based care—including proper micronutrient support, selective antiviral use, and clear diagnostic protocols—can minimize risks and improve quality of life. Continued pharmaceutical research holds promise for more effective treatments.

Categories: health